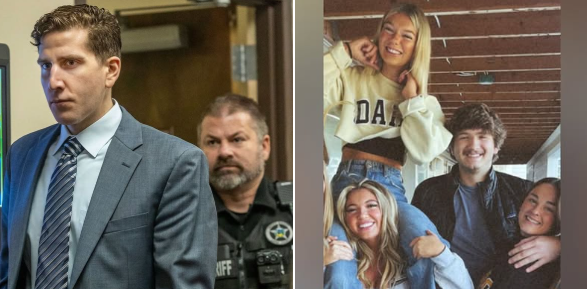

In a moment of chilling finality that has reverberated across Idaho and the nation, Bryan Kohberger stood in an Idaho courtroom this past Wednesday and admitted—without hesitation or remorse—to the brutal slaying of four University of Idaho students: Madison Mogen, Kaylee Goncalves, Xana Kernodle, and Ethan Chapin. Each name, once linked to the promise of youth, community, and futures not yet written, was uttered with judicial precision as the judge asked Kohberger to confirm responsibility. He answered each query with a single, eerily emotionless word: “Yes.” This somber courtroom exchange cemented one of the most harrowing and widely followed homicide cases in recent memory, as Kohberger entered a guilty plea to four counts of first-degree murder, sealing a deal that will spare him from execution by firing squad—a punishment still on the books in Idaho, though rarely invoked.

Wearing a tie and slacks, Bryan Kohberger, who until this moment had maintained a stoic and defiant legal strategy, stood to answer questions posed by the judge, his voice stripped of inflection. The judge, in a procedural reminder of the court’s expectations, noted that Kohberger was not required to stand. But Kohberger remained upright, a gesture that might have been interpreted as deliberate control or perhaps rehearsed submission. In any other setting, such an act might have appeared courteous. In this room, it read as unsettling—underscoring a demeanor that has perplexed, angered, and disturbed many since the murders first came to light.

As the judge recited the names of the victims—Madison Mogen, Kaylee Goncalves, Xana Kernodle, and Ethan Chapin—each one was met with the same cold response. Yes, Kohberger confirmed, he had killed each of them. Yes, he was guilty. Yes, he was not under the influence of any substance that could affect his judgment. And yes, he understood what he was agreeing to. In that solemn exchange, the weight of months of investigative work, community grief, courtroom tension, and national speculation collapsed into a verdict that left the victims’ families with a mixture of closure and fresh sorrow.

The plea deal itself has been the subject of immediate and intense scrutiny. To some, it represents an act of legal pragmatism—a way to avoid the prolonged trauma of a public trial. To others, it feels like a jarring escape from the ultimate accountability that many had expected Kohberger to face. Idaho is one of the few states where death by firing squad is still authorized under specific circumstances. This fact alone had positioned the case as one of national curiosity, especially amid ongoing debates about the ethics and efficacy of capital punishment. The decision to forgo that route—and instead accept Kohberger’s guilty plea—raises profound questions about justice, closure, and whether the legal system can ever truly account for the devastation wrought on four families, a university, and a shaken rural community.

The methodical nature of the hearing was itself jarring. There was no dramatic confession, no breakdown of emotion, no elaboration on motive. Just a series of questions and answers—delivered with a surgeon’s detachment, as though Kohberger were acknowledging facts rather than confessing to one of the most heinous acts in Idaho’s criminal history. This lack of visible remorse has not gone unnoticed. In fact, for many watching the case closely, it has only deepened the sense of revulsion and disbelief.

The backdrop to Kohberger’s plea is the horrific night in November 2022 when Madison Mogen, Kaylee Goncalves, Xana Kernodle, and Ethan Chapin were found brutally murdered in their off-campus residence. Authorities later revealed that the victims had likely been asleep when they were attacked—an element of the crime that intensified its barbarity and introduced a dimension of helplessness that haunts the case to this day. That Kohberger now admits to committing the killings “as they slept” removes any lingering ambiguity and forces a confrontation with the raw reality of what occurred behind the walls of that house.

The implications of a guilty plea in a quadruple homicide case are far-reaching. For law enforcement, it brings a definitive end to a high-profile manhunt and investigation that demanded resources and attention on an extraordinary scale. For the legal system, it sidesteps what would have undoubtedly been a lengthy and emotionally grueling trial. But for the victims’ families, it delivers something far more complicated. The avoidance of a trial means the circumstantial and psychological details behind the murders may remain unexplored. The reasons why Kohberger did what he did—the how, the why, the lead-up—remain locked away in the mind of a man now convicted but still largely enigmatic.

In pleading guilty, Kohberger has spared himself the death penalty, but in doing so he has also altered the public narrative. No longer is this about a man presumed innocent until proven guilty. No longer is this about speculation or emerging evidence. It is now a case about acknowledgment, admission, and a justice system that must balance the raw human need for retribution with its own procedural imperatives.

Idaho’s death penalty statutes, which allow for execution by firing squad, were reexamined intensely in the months leading up to the plea. The gruesome nature of that method—seen by some as a relic of another era—had led to polarizing discussions about its morality, legality, and practical application. In sparing Kohberger from that fate, prosecutors likely weighed the certainty of a conviction against the uncertain outcome of a trial and the inevitable appeals process that would follow a death sentence. It is not uncommon for such cases to stretch on for decades, often forcing the families of victims to relive the trauma again and again.

Still, the public response to the plea deal has been far from unified. For some, the idea that a man who murdered four young students in their sleep could ultimately spend his life in prison—potentially shielded from harm, with access to resources and legal counsel—is offensive. For others, there is a grim satisfaction in knowing he will live with the consequences of his actions for the rest of his natural life. There is no tidy resolution to crimes of this magnitude, and perhaps no punishment that can ever feel equal to the pain inflicted.

The identities of the victims—Madison Mogen, Kaylee Goncalves, Xana Kernodle, and Ethan Chapin—have become indelible in public memory. They were not anonymous figures. They were friends, siblings, children, students. Madison and Kaylee were lifelong friends, described by those who knew them as “inseparable.” Xana was known for her vivacious energy, while Ethan, the only male among the victims, brought warmth and a sense of humor to every gathering. Their names now appear in candlelight vigils, on the walls of dorms, in moments of silence at sporting events and graduations they will never attend. To say that Kohberger’s admission has closed a chapter would be misleading; it has only solidified the incomprehensibility of their loss.

There is also the question of precedent. In a legal environment where plea deals in capital cases are increasingly common, some see this outcome as part of a larger pattern: the gradual retreat from the death penalty in states where it remains legal. Whether this signals a shift in prosecutorial priorities or simply reflects the unique factors of this case remains to be seen. What is certain is that the public’s appetite for answers is unlikely to subside. Without a trial, there is no formal airing of the evidence, no cross-examination, no opportunity to understand the sequence of events in forensic detail. What prompted Kohberger to choose his victims? How did he carry out the crime undetected for so long? What signs, if any, did he exhibit beforehand? These questions linger, gnawing at the edges of the official narrative.

For now, the legal system has done what it can. A guilty plea, four counts of murder acknowledged, a death penalty averted. Bryan Kohberger will serve a life sentence—one likely defined by isolation, notoriety, and the cold absence of redemption. And yet, in court, there was no apology. No reflection. No appeal to the families of the victims. Only “Yes.”

The absence of emotion in Kohberger’s responses may not be legally significant, but it is symbolically profound. It stands in stark contrast to the raw humanity of the four lives he took and the lives left in ruins by his actions. The silence that followed each confirmation of guilt echoed more loudly than any outburst might have. It was a silence filled with mourning, with lost potential, with the irrevocable stillness of four college students who will never graduate, never return home, never grow old.

In the wake of the plea, the University of Idaho community has begun another cycle of mourning. The campus, once cloaked in fear as the investigation unfolded, is now blanketed in solemnity. Memorials remain. Flowers continue to appear. And students walk past buildings and classrooms that were once shared with the victims, now carrying an invisible burden of remembrance.

Bryan Kohberger has confessed. But in doing so, he has not offered peace—only confirmation. The justice system has recorded his guilt, but justice itself, as the families and the public must now grapple with, is something far more elusive.